By Kim Hirsch-Hoffmann

#réinventonslescodes is the title of an ambitious project launched in 2022 by Ms. Shani Benoualid, digital and social networks advisor at the DILCRAH (interministerial directorate for the fight against racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-LGBT hate). The goal of this code is to change awareness and behavior in video games, act against online toxicity and change the codes of gaming. We are ten students who participated in the elaboration of this code alongside governmental actors, developers, and professionals of the video game world.

This article aims to raise awareness about cyberbullying in the gaming world, and to explain the #reinventthecodes project that will be released in 2023.

The world of video games

In 1950, the concept of the video game was born: a game on a video device allowing its user to interact with the machine in a playful way. In 2022, the number of gamers in the world is estimated at more than 3.2 billion people, almost half of humanity[1]. In 2021, the mobile video game sector will bring in more than 180 billion euros in sales[2]. In France, more than 36 million people play at least occasionally, with a male-female parity[3]. These figures show us the social and economic importance that video games have today on our societies.

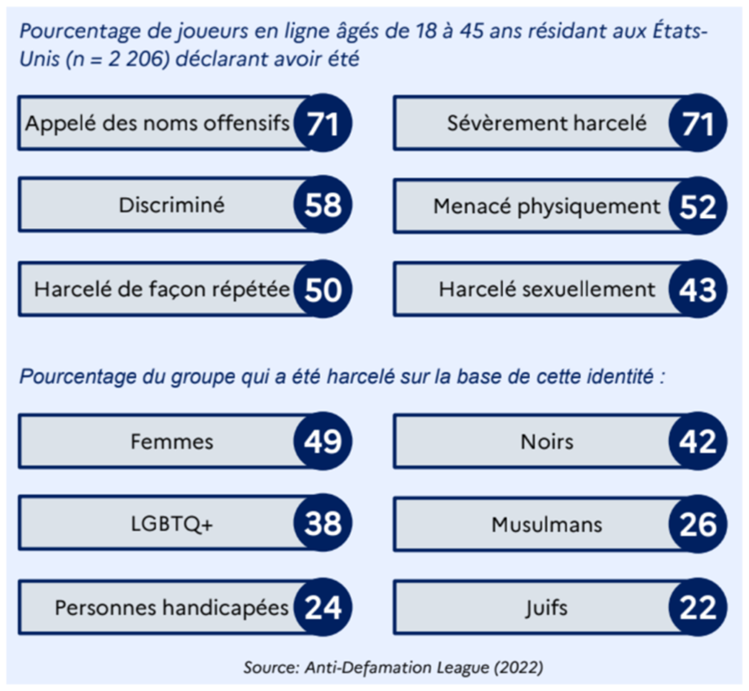

Like social networks and the rest of the cyberworld, video games are not immune to the dangers of the net: online hate, cyber-stalking, racism, misogyny, etc. In the E.U., 80% of Internet users have read hate speech online and 40% have felt attacked on social networks (Gagliardone et al, 2015). In the U.S., 74% of adults who play online games have experienced some form of harassment (Anti-Defamation League, 2019). Thus, 1 in 10 gamers report having ever had depressive or suicidal thoughts because of such violence, 1 in 4 female gamers no longer wish to play because of online misogyny. Nearly 6 out of 10 female gamers use a male-sounding screen name to avoid sexist insults, harassment, or sexual violence, like sending unsolicited nude photos (Reach3 Insights and Lenovo, 2021)[4]. Toxicity on online video games is not anecdotal, it is part of a global problem of online hate.

In this regard, the French government adopted the ‘Avia’ law in June 2020[5] to fight against hateful content on the Internet. An observatory of online hate[6] has also been set up to analyse and quantify hateful content, monitor its evolution, and share this information with the public.

The video game industry has also participated in this effort, setting up reporting and banning features and encouraging their users to be ‘fairplay’. However, the steps taken by developers, however, remain insufficient. The Anti-Defamation study of 2022 in the United States shows that harassment remains a common practice on video games.

Faced with cyber-violence, it is necessary that Internet users and gamers, as citizens, become aware of their actions and show civic mindedness.

Video games: a fertile ground for online hate

The #réinventonslescodes project was launched in April 2022 by the DILCRAH (Interministerial Directorate for the Fight against Racism, Anti-Semitism, and Anti-LGBT Hatred) in collaboration with the DINUM (Interministerial Directorate of Digital) and the DITP (Interministerial Directorate of Public Transformation). It follows a study conducted by the DITP “Civisme et Jeux vidéo, l’éclairage des sciences comportementales” on online hate and toxicity in video games.

The study identifies four determinants of online toxicity: the online environment (anonymity), the game environment (violent and competitive mechanisms), the social environment (movement effect), and the player himself or herself (psychological profile).

For gamers, the game environment is often seen as a source of escape, as the study indicates. The anonymity of the pseudonym and the physical distance from the fictional characters that the players embody blur the social rules. John Suler (2004) speaks of the “online disinhibition effect”. The dissociative anonymity and sense of invisibility cause players to become morally disengaged.

The gaming environment is a major source of frustration and stress for gamers. The study notes that most toxic behaviors are observed in MOBAs (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena), team-based multiplayer games that are often highly competitive. The desire to win, the lack of communication skills and the resulting conflicts within the team lead to a loss of control, called tilt. The testimony of a player interviewed sheds light on this subject:

“If you think about League of Legends, it’s incredible, it’s almost euphoric when you win. But you feel so bad when you lose, when the other team runs you over because of some asshole on your team, when you lose 20/30 minutes of your life where you didn’t have you didn’t have any fun at all.”

The environments faced by gamerrs are conducive to aggressive, toxic, and sometimes even criminal behaviour. The lack of reaction from players to these behaviors is linked to a minimization and trivialization of them. Bad language is part of the game, sexist and misogynistic language is ‘just’ a heavy joke.

The goal of the project was to consider each of these factors and all the actors present in video games (players, mediators, developers), to propose realistic solutions to create new norms and raise the awareness of players.

A code of conduct for the GG (aka Good Gamer)

The project took place in three phases: the introductory phase with the presentation of the studies and the stakes, the phase of elaboration of the main themes and messages of the code and the final phase of selection of the communication campaign.

A major challenge in this project was to come up with a clear message about the limits of what is acceptable and legal, while keeping a positive form that would not alienate the player. Many people are unaware of the law and sometimes wrongly think that the gaming world is not subject to it.

First, we had to define the term toxicity concretely to better orient the message of the code. Is getting mad at a game a form of toxicity? Are words like ‘incompetent’, ‘loser’, etc. part of the toxicity spectrum? The world of gaming is particularly harsh, and gamers rarely hide their extreme displeasure. So much so that some consider this form of verbal abuse to be an integral part of the game.

Aware of the gaming community’s lack of receptivity to government messages, we came up with a code keeping in mind the image of the GG, the Good Gamer. The goal is to allow the gamer to realize that they are responsible for their actions. Awakening empathy is a particularly difficult exercise in the context of the Internet, with the challenges of invisibility and anonymity. We therefore decided to focus on the player’s ability to overcome the tilt, to evaluate themselves and to become a leader both technically and morally. In short, to create a new ideal of player that would be inspiring and motivating, without adopting a punitive and judgmental tone.

This positive approach engages everyone, whether it’s on video games or on our networks. We are all citizens with rights and duties, and human beings with strengths and vulnerabilities, let’s be Good Gamers and Good Web users.

#réinventonslescodes

Image source: https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-48750608

[1] Arthur Aballéa. 7 chiffres clés sur le gaming en France et dans le monde en 2022. Blog du modérateur, March 2022. https://www.blogdumoderateur.com/chiffres-cles-gaming-france-monde-2022/

[2] TechnoFinance. Les revenus des jeux vidéo : combien cela rapporte ? June 2022. https://www.techno-finance.fr/revenus-jeux-video-combien-rapporte/

[3] Arthur Aballéa, 2022.

[4] JdG. 59 % des joueuses cachent leur genre pour ne pas subir de harcèlement. May 2021. https://www.journaldugeek.com/2021/05/23/59-des-joueuses-cachent-leur-genre-pour-ne-pas-subir-de-harcelement/

[5] Vie Publique. Réseaux sociaux : un observatoire de la haine en ligne pour analyser les discours haineux. October 2022. https://www.vie-publique.fr/en-bref/276769-observatoire-de-la-haine-en-ligne-mise-en-place-des-groupes-de-travail

[6] CSA. Observatoire de la haine en ligne : analyser pour mieux lutter. October 2020. https://www.csa.fr/Informer/Toutes-les-actualites/Actualites/Observatoire-de-la-haine-en-ligne-analyser-pour-mieux-lutter