By Marine Pichon

This paper was written for the course TERRORISTS, KINGPINS AND CYBERCRIMINALS: THE GLOBAL SECURITY RISK OF VIOLENT NON- STATE ACTORS taught by Christina SCHORI LIANG at Sciences Po Paris (1st semester of 2023).

Picture taken from Moga, Ezekiel. “A Historical Assessment of Cybercrime in Nigeria: Implication for Schools and National Development”. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, Volume 9, Issue 9, 2021.

KEY POINTS

- Since the 1990s, increased digitalization, urbanization and high unemployment have led to the structuration of numerous West African cybercriminal groups.

- These non-state threat actors typically engage in financially-motivated and unsophisticated cyber operations leveraging social engineering, scams and extortion. These cyberattacks are becoming increasingly sophisticated due to the wider accessibility of more powerful malware sold or leaked on the Dark web.

- West African cybercrime leads to significant economic losses, and to larger governance, societal and security challenges for states since these ecosystems are often well connected to other more traditional forms of organized crime.

- In order to properly answer to these threats, states must acknowledge that this is a phenomenon rooted within transnational underground dynamics but also facilitated by the lack of regulations and cybersecurity defenses domestically.

INTRODUCTION

$8 Trillion. This is the estimated global cost of cybercrime predicted for 2023. If it was measured as a country, cybercrime would be the world’s third-largest economy after the U.S. and China. Since almost 30 years, global cybercrime has become a significant threat to individuals, businesses, and governments worldwide. Far from being a new phenomenon, cybercrime nonetheless remains a highly modern challenge, deeply connected to the rhythm of technology and constantly in evolution to bypass cybersecurity defenses and new regulations with increasingly sophisticated malware and techniques. This growth in cybercriminal activities can be explained by a variety of factors, ranging from the increasing ease of access and reliance on technology to the significant average profitability of these operations. Indeed, according to a study released in 2018 by Dr. Michael McGuire (1), cybercriminals earning the most are making as much as much as $2 million a year, with lower wages hovering around 75,000 a month (2). In addition, cybercrime is both easily accessible (including for script kiddies) and less risky. Indeed, compared to traditional criminal activities, cybercrime does not involve physical violence, nor proximity with the target, offering a comfortable anonymous situation to the threat actors and thus reinforcing its attractiveness for financially motivated individuals.

Although cybercrime is a global challenge, rooted in numerous geographical hotbeds around in the world (Russia, Eastern Europe, Ukraine, Romania, Turkey, Nigeria, Brazil, China, North Korea, among others), every region responds differently and features local dynamics worth analyzing. By understanding how the threats are evolving and what kind of harm they are causing in each region, they can be defeated more effectively. In this paper, we will mostly study West African countries and focus on non-state threat actors.

Africa has surpassed other regions such as North America, South America, and the Middle East in terms of the number of Internet users, with over 500 million users. This translates to approximately 38% of the population and is expected to increase in the future due to accelerated digitalization. West African cybercrime surfaced in the 1990s through the penetration of Internet in the largest Nigerian cities such as Lagos. The extension and sophistication of the cybercrime phenomena in this country even made Nigeria ranked at the unenviable third place in the 2007 ranking of cybercrime in states after the UK and the US (3). This dynamic then later spread to neighboring countries such as Ghana, Cameroon, Benin, Senegal and Burkina Faso after the 2000s.

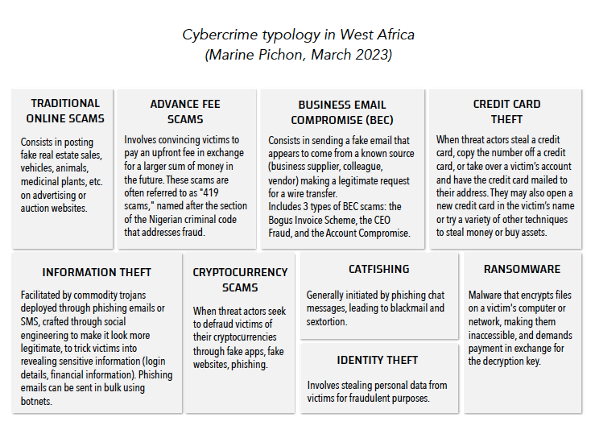

What should be noted however is that, while cybercrime by definition includes all activities that are committed through the use of digital technologies or the Internet (such as hacking, cyberstalking, identity theft, phishing, malware attacks, and various forms of online fraud), West Africa is almost exclusively vested in cyber fraud for financial gain, ie. the use of deception to tout and defraud people, which typically requires less technological skills but sufficient social skills to attract and misdirect victims (4). This specialization for instance differs from other hotbeds around the world, such as the Russian ecosystem which is notoriously more vested in ransomware, information theft and extortion (5). Throughout this paper, we will favor the use of the term ‘cybercrime’ compared to cyber fraud, in order to remain inclusive and to coincide as well with the terminology used by the cybersecurity industry which for instance distinguishes between cybercrime (leveraged for lucrative purposes by threat groups) and cyberespionage (most often leveraged by state-sponsored actors or intelligence agencies).

UNDERSTANDING THE ROOTS OF WEST-AFRICAN CYBERCRIME

Over the last three decades, Africa has experienced an unprecedented wave of technological diffusion and innovation. In 1995, there were only 16.000 Internet users in all of Africa, compared to over 700 million Internet users on the continent, placing the region ahead of other regions such as North America, South America, and the Middle East (6). In 2021, Nigeria had the highest number of Internet users in West Africa, with an estimated 123.5 million people online – 60% of its population (15.8 million for Ghana and 13.9 million for Côte d’Ivoire (7)). This fast-paced deployment of Internet access in West African urban environment has been driven by two main factors: on one hand, the growth of cyber cafes (50 cyber cafes in 2000, 10.000 by 2007), which played a key role between the 1990s and 2000s. On the other hand, the rise of mobile phones starting from 2006-2007. As of 2021, there were over 477 million unique mobile subscribers in Africa (8), a trend which expected to further grow in the coming years given the accelerated adoption by African societies of mobile banking. Yet, this fast-paced digitalization also embodies an important issue, especially because cybersecurity parameters and standards are often insufficient or simply lacking. According to Interpol, in 2021, 90% of African businesses were operating without the necessary cybersecurity protocols in place, enabling threat actors to exploit increasing vulnerabilities and earn significant financial gains. Unsurprisingly, this digital divide has been enhanced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, since the 1990s, the growing rate of digital transformation in West Africa has been facilitating the emergence of new form of crimes reliant on cyber means, benefiting from new attack vectors and opportunities.

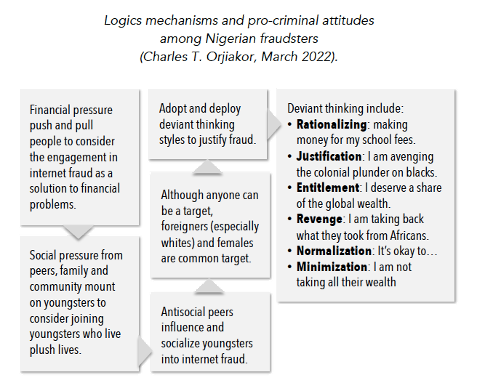

In addition to digitalization, the structuration of a true cybercriminal ecosystem has been enhanced by a great diversity of factors intrinsically linked to the local economic, social, demographic, political and legal realities rooted in the region. Academics such as Anah Bijik Hassan identified urbanization, high unemployment, quest for wealth, poor implementation of cybercrime laws, inadequately equipped law enforcement agencies, and negative role models as some of the causes of proliferated cybercrimes in Nigeria (9). Looking at a more micro level, Charles T. Orjiakor recently gave a detailed description of the pro-criminal attitudes and cognitions of Internet fraudsters in Nigeria and identified some striking characteristics and thinking patterns among them (10). According to his study, cybercriminals commonly identified friends and close associates as the links through which they got introduced to cyber fraud.

This influence sometimes corresponds to a direct or indirect pressure from peers and actors in the local community who flaunt wealth, or who are deemed more responsible as they are able to provide for their families. Unsurprisingly, the financial aspect is the dominant motivation mentioned by threat actors whether it is needed to meet their own life demands (such as education fees) or to support their families. This pull factor is all the stronger due to the relative lack of opportunities felt by many West African millennials, who turn to cyber fraud as a mean of realizing their aspirations. According to Benjamin Okorie, the tight grip of leadership cults in African countries, which typically allows only a handful of people into leadership positions and keeps the young and innovative millennials out, particularly fuels the inclination of the youth towards cyber fraud (11). Finally, as Charles T. Orjiakor explains, Nigerian cybercriminals also tend to consider their actions as getting recompense for the injustice done to their ancestors. Thus, Internet fraud is perceived as a tool through which social justice is achieved by making Westerners pay some form of reparation for their evil past (12). These findings are extremely similar to those of Frédéric-Jérôme Pansier and Emmanuel Jez who studied Beninese cybercriminals (13). All of these psychological, economic and social vectors tend to normalize cybercrime and minimize its impacts, thus further reducing the barrier of entry into fraud for others.

These diverse motivations thus lead to the structuration of entire sub-communities or gang-like structures centered around cybercrime activities. The size of these gangs is variable. In Ivory Coast, cybercriminals are generally organized into small networks (three or four people), and according to the Ivorian police, arresting a member of the network often leads to dismantling the entire network. At the contrary, Nigerians tend to be structured into international mafia networks. For instance, identified in January 2022 by the Interpol’s Global Financial Crime Taskforce, the threat group tracked as SilverTerrier was a syndicate of over 400 people (14). Another example is the Black Axe Confraternity15, which surfaced in the 1970s as a traditional mafia in Benin and which shifted into a transnational cybercrime group composed of at least 70 people, some of which were arrested by Interpol in 2022 as well (16). Most of these groups gather young males (around 90%), often aged between 15 and 30 years old (17), either students, unemployed individuals, or young workers looking for extra money, and finally noticeable in the streets driving exotic cars (18). Interestingly enough, fraudsters are named differently depending on their locations. While cybercrime is called “Yahoo yahoo” in Nigeria (“yahoo boys” for fraudsters), it is named “Sakawa” in Ghana (19), “Faymania”(20) in Cameroon or “gay man” ou “Computerman” in Benin (21). Finally, these communities generally tend to mix cybercriminal activities with other forms of delinquency. According to Joshua Aransiola, who notably studied the mystic practices of Yahoo Boys in Nigeria, certain cybercriminals will go as far as sacrificing a parent or a sibling, perform children kidnappings for ritual killings, or sell parts of their bodies in order to ensure the success of their cyber operations (22). The adoption of traditional spiritual means like voodoo or juju, sometimes referred as “Yahoo Plus” rituals, is supposed to help “hypnotize” victims and guarantee luck. Other forms of rituals performed include sleeping with pregnant women or mad women, sleeping in a coffin for certain numbers of days, sleeping in the cemetery, consulting a spiritualist, a diviner or an oracle etc. (23)

UNDERSTANDING THE ARSENAL: MALWARE PROLIFERATION AND SUPPLY CHAIN

As mentioned in the introduction, one of the main characteristics of the cyber threat landscape in West Africa is that it originally consisted of mostly fraud and scam operations. As explained by Trend Micro, a notorious cybersecurity editor based in Japan, West African cybercriminals are particularly good at defrauding victims for financial gain (24), relying on social engineering and social skills to attract and misdirect victims. Most cyberattacks emanating from this region can thus be categorized under the following types:

This overreliance on scams initially made the West African cybercrime ecosystem stand out compared to other cybercrime hotbeds around the world which generally tend to rely more on hacking using trojans and malware (25). It should nevertheless be noted that this distinction is becoming increasingly outdated, with the emergence of a new breed of West African cybercriminals more technically proficient since a couple of years. Besides possessing stronger technical know-how, these threat actors engage in more complex types of cyberattack involving malicious software (ransomware, infostealer, banking trojan) and requiring preliminary reconnaissance and in-depth research on the targets. According to TrendMicro which notably studied this shift, these next-level cybercriminals usually purchase keylogging software and hire encryption service providers from Russian underground forums and marketplace. This technical refinement is not surprising per se but embody an important aspect when it comes to understanding cybercrime: this is a global phenomenon. The interconnectedness between West African fraudsters and transnational malware supply networks both leads to the sophistication of attacks (access to a wider diversity of malware, generally more sophisticated than those developed locally) and to the lowering of the entry barrier into cybercrime (with malicious tools now sold off the shelf, ready to use, sometimes with YouTube tutos for non-technical people on Amazon-like marketplaces hosted on the Dark web or on Russian Telegram channels). For instance, according to Interpol, numerous threat actors in Africa are deploying spam run campaigns with enclosed trojan stealers such as Lokibot, Agent Tesla or Fareit, which are strains either sold on Russian marketplaces ($182 a month for Agent Tesla) or available in open sources (26). Thus, the structuration of the malwareas-a-service model, which transforms a malware into a commodity worth renting in exchange for a fee, and the diffusion of this new supply chain around the world encourage West African cybercriminals to continue honing their know-how, skill sets, and arsenals, adding an extra layer of complexity when it comes to combating West African cybercrime.

UNDERSTANDING THE CONSEQUENCES OF WEST AFRICAN CYBERCRIME

Unsurprisingly, cybercrime operations emanating from West Africa lead to monumental financial losses, both domestically and abroad. It should be nonetheless noted that it is quite hard to have a precise estimation of the financial cost for African states and organizations. Indeed, West African hackers are not the only actors targeting West African organizations: since 90% of African businesses are operating without the necessary cybersecurity protocols in place, they have become a target of choice for financially motivated cybercrime groups from all over the world and not only African fraudsters (27). For instance, in 2019, a wave of cyberattack on Nigerian financial institutions was attributed to a group known as “Silence” (28), which is believed to be based in Russia (29). More recently, the Nigerian betting site Bet9ja was breached by major Russia-based ransomware operation BlackCat (30). It is worth noting that not all cyberattacks are reported or detected, so the true scope and origin of attacks targeting West African entities may not be fully known. Yet, regardless of the origin of the attack, cybercrime is heavy with consequences. Research from a Kenyan IT cybersecurity company Serianu highlighted that cybercrime reduced GDP within Africa by more than 10%, at a cost of an estimated 4.12 billion USD in 2021 (31). A study conducted by International Data Group Connect showed that each year, cybercrime cost the Nigerian economy 500 million dollars, $50 million for Ghana (32). Indirectly, cybercrime is also providing a dent on West African countries’ image, having a negative impact on investments and on the confidence level in the banking sector and affecting the countries’ development progress (33). According to Jean- Jacques Bogui, who particularly studied Ivory Coast cybercrime, the first companies to be affected by these negative consequences are the Ivorian Internet service providers (ISPs), which are increasingly blacklisted when their IP addresses are recognized on certain ecommerce sites, thus blocking any transactions (34).

But cybercrime also embodies crucial implications for state governance and society. When cyberattacks target critical infrastructures such as power grids or telecommunications networks, this leads to even more significant impacts on individuals and society at large. For instance, last September 2022, a major unattributed cyberattack affected the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), resulting in some customers being unable to buy power and others having their power off for days (35). Similarly, when cyberattacks target public institutions such as ministries or government agencies, this leads to increased loss of confidence and trust in the government as a whole. Cybercrime also embodies a societal and educational issue, as most fraudsters are extremely young. By versing into fraud and considering it as a mean to avoid poverty, it creates a vicious circle further encouraging others to join cybercrime, and additionally depriving the West African cybersecurity sector of potential workforce technically proficient (36). Finally, cybercrime also fuels the growth and integration of West African youth into more traditional organized criminal networks operating in the illegal wildlife, mineral, and human smuggling and trafficking markets. The money earned from cybercrime is generally reinjected and laundered in other forms of traffics or corruption bribes. For example, a 2021 report from the Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA) highlighted that proceeds from cybercrime were increasingly used to finance terrorist groups and drug traffickers in this region (37). Therefore, cybercrime weakens government capacity by leeching away resources, capacity and legitimacy required for good and democratic governance.

RECOMMANDATIONS

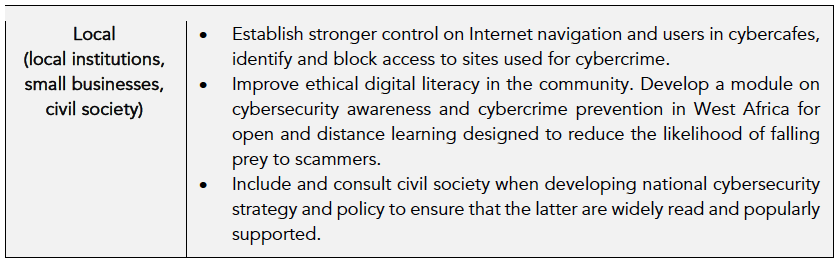

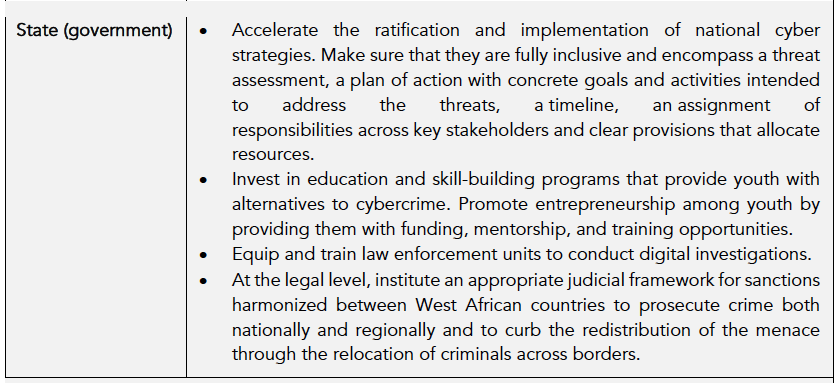

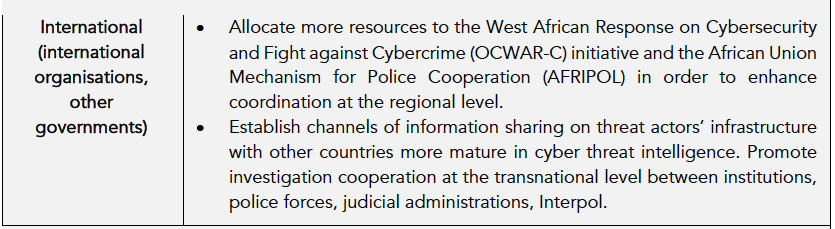

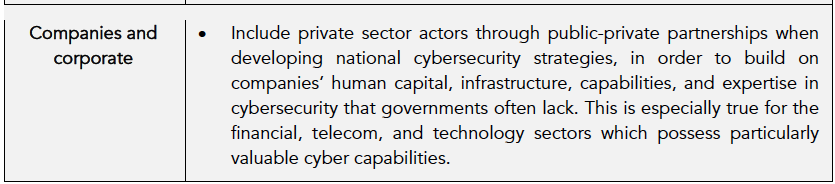

Facing these significant challenges, West African governments must act and adopt innovative answers to both reduce the easiness of cyberattacks through cybersecurity regulations, sanction organized groups through legal means and offer attractive alternatives to reorientate young fraudsters through holistic policies.

CONCLUSION

Although West African cybercriminals have been primarily associated with simple types of fraud, they are increasingly engaging in more sophisticated and complex malicious activities. As we have seen, these cybercriminals are leveraging their social engineering skills, ingenuity, and access to various tools and services, often available on transnational underground marketplaces, to steal significant amounts of money through attacks on individuals and businesses globally. Because of its relative success and easiness, cybercrime is increasingly attractive for young West African looking for wealth, opportunity and prospect, thus embodying a crucial challenge for West African societies, state governance and national economies. Because cybercrime is a transnational phenomenon, answers brought forward by governments should encompass all levels: local to transnational and include the civil society and private-sector actors.

(1) McGuire, Mike. Into The Web of Profit. An in-depth study of cybercrime, criminals and money. Bromium, 2018.

(2) It is important to note that the actual profit for a cybercriminal may be lower than these estimates, as there are costs associated with carrying out a cyberattack, such as purchasing or developing the tools and techniques needed to carry out the attack, and dividing the profits for the rest of the team.

3) Cisse, Abdoullah. “Exploration sur la cybercriminalité et la sécurité en Afrique : État des lieux et priorités de recherche : Synthèse des rapports nationaux”. Centre de recherches pour le développement international, January 2011.

(4) Al-Shalan, Abdullah. “Cyber-crime fear and victimization: An analysis of a national survey”. Mississippi State University, 2006.

(5) Okorie, Benjamin et al. “Neo-Economy and Militating Effects of Africa’s Profile on Cybercrime”. International Journal of Cyber Criminology, Vol 13 – Issue 2, December 2019.

(6) Interpol, African Cyberthreat Assessment Report 2021, October 2021.

(7) Idem.

(8) Idem.

(9) Hassan, Anah Bijik et al. « Cybercrime in Nigeria: Causes, Effects and the Way Out”, ARPN Journal of Science and Technology, vol. 2(7), 626 – 631, 2012.

(10) Orjiakor, Charles T., et al. “How do internet fraudsters think? A qualitative examination of pro-criminal attitudes and cognitions among internet fraudsters in Nigeria”, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33:3, 428-444, March 2022.

(11) Okorie, Benjamin et al. “Neo-Economy and Militating Effects of Africa’s Profile on Cybercrime”, International Journal of Cyber Criminology, Vol 13 – Issue 2, December 2019.

(12) Idem.

(13) Pansier, Frédéric-Jérôme et al., La cybercriminalité sur Internet, PUF, p. 127, 2000.

(14) Brewster, Thomas. “800,000 Passwords, 50,000 Targets: A Huge Nigerian Fraud Operation Busted”. Forbes, January 2022.

(15) Crowstrike Global Intelligence Team. “Intelligence Report: Csir – 18004 – Nigerian Confraternities Emerge As Business Email Compromise Threat.” Crowdstrike, 20 March 2018.

(16) Interpol, “International crackdown on West-African financial crime rings”. Interpol News, 14 October 2022.

(17) Okeshola, Folashade B. et al. “The Nature, Causes and Consequences of Cyber Crime in Tertiary Institutions in Zaria-Kaduna State, Nigeria”. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, Vol. 3 No. 9; September 2013.

(18) Orjiakor, Charles T., et al. “How do internet fraudsters think? A qualitative examination of pro-criminal attitudes and cognitions among internet fraudsters in Nigeria”, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 33:3, 428-444, March 2022.

(19) Coomson, Joseph. “Ghana: Cyber Crimes in Ghana”, Ghanaian Chronicle (Accra), October 2006.

(20) Oumarou, M. “Brainstorming advanced fee fraud: ‘Faymania’ – the Camerounian experience”, in Current trends in advance fee fraud in West Africa, Nigeria: EFCC, 2007.

(21) Tasso Boni, Florent. «La cybercriminalité au Bénin : une étude sociologique à partir des usages intelligents des technologies de l’information et de la communication», Les Enjeux de l’Information et de la Communication, n°15 – 2B, 2014.

(22) Aransiola, Joshua. “Understanding Cybercrime Perpetrators and the Strategies They Employ in Nigeria”. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(12):759-63, December 2011.

(23) N’Guia, Jean-Claude. “Monde occulte et enrichissement rapide des jeunes cybercriminels à Daloa”. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, Volume, 10, Issue 9, 2022.

(24) TrendMicro and Interpol. Cybercrime in West Africa Poised for an Underground Market, Joint Research Paper, 2017.

(25) Cisse, Abdoullah. “Exploration sur la cybercriminalité et la sécurité en Afrique : État des lieux et priorités de recherche : Synthèse des rapports nationaux”. Centre de recherches pour le développement international, January 2011.

(26) Interpol, African Cyberthreat Assessment Report 2021, October 2021.

(27) According to The State of Ransomware 2022 survey report conducted by cybersecurity company Sophos, 71 per cent of Nigerian organisations were hit by ransomware in 2021.

(28) “Silence hacking group targets banks in Nigeria, others”, The Sun Nigeria, 14th January 2020.

(29) Group-IB. Silence 2.0: Going Global, August 2019.

(30) DAW EMPIRE [@dawempire]. “Bet9ja’s Website Hacked By Russian Blackcat Group, LASG Responds”. Twitter, 7 April 2022.

(31) Djade, Charles. “L’Afrique a perdu 10% de son PIB en 2021 du fait de la cybercriminalité”, SciDevNet, 6 April 2022.

(32) Idem.

(33) Okorie, Benjamin et al. “Neo-Economy and Militating Effects of Africa’s Profile on Cybercrime”, International Journal of Cyber Criminology, Vol 13 – Issue 2, December 2019.

(34) Bogui, Jean-Jacques. « La cybercriminalité, menace pour le développement. Les escroqueries Internet en Côte d’Ivoire », Afrique contemporaine, vol. 234, no. 2, 2010.

(35) Dogbevi, Emmanuel K..”ECG systems hacked with ransomware”, Ghana Business News, 1 October 2022.

(36) Moga, Ezekiel. “A Historical Assessment of Cybercrime in Nigeria: Implication for Schools and National Development”. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science, Volume 9, Issue 9, 2021.

(37) Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA). Typologies Report: Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing through Corruption in West Africa. November 2022.